STIFTUNG

WOLFRAM BECK

WOLFRAM BECK

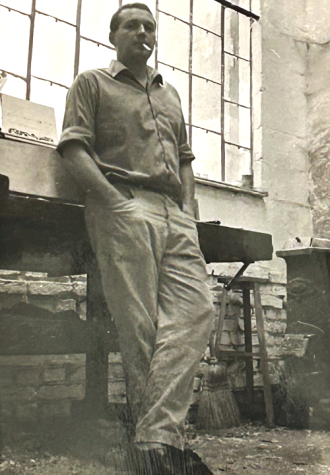

Wolfram Karl Richard Beck 30.4.1930 Greiz – 10.1.2004 Berlin

Wolfram Beck was the firstborn child of a merchant and a master embroiderer. In 1944, at the age of 14, he was drafted from his humanities-focused high school into the anti-aircraft artillery service, where he was seriously wounded by a grenade. He spent a long time in a military hospital, an experience that never left him. His father was killed on the Eastern Front in 1945.

After completing a woodturning apprenticeship in Greiz, he continued his training as a wood sculptor at the Empfertshausen Carving School in the Rhön Mountains under Bauhaus student Wilhelm Löber for the next two years. Life in the GDR was unimaginable for him. After receiving his certificate, he walked across the green border to the West. He then financed the rest of his schooling with hard manual labor at the Fritz-Heinrich coal mine in Essen and in the port of Hamburg, eventually graduating with a “late high school diploma.” His first opportunity to earn a living as a sculptor came in 1951, when he designed exhibits for the “Great Health Exhibition Cologne,” including representations of the human vascular system. Until 1955, he worked as a sculptor's assistant for Professor Willy Meller in Cologne.

From 1955 to 1960, Beck studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin under Professor Paul Dierkes. During this time, he created numerous wooden sculptures, whose motifs he later varied using other materials. He completed his studies with the title of master student.

In keeping with the tradition of wood carving, he designed tombstones during this period. This involved determining the shape and proportions of the wooden stele, memorial stone, or monument. Suggesting a memorial inscription or Bible quote and selecting and setting the font were also traditionally part of the scope of work.

After completing his studies, Wolfram Beck received commissions for portrait busts for private clients, as well as invitations to participate in tenders and commissions from the Kunst am Bau program. In 1965, he was commissioned to create the first Golden Camera television award for Axel Springer Verlag. The award was presented for the first time in 1966.

In 1965, he married Bärbel Wendt, an actress who came from a family of entrepreneurs. Financial support from his father-in-law allowed Beck to devote himself to his art in the decades that followed without having to worry about making ends meet. The couple had two children.

In the early 1970s, he lived and worked in the Lüneburg Heath. From the early 1980s onwards, the family lived in Berlin and in Tourrettes-sur-Loup in southern France. Like many artists before him, Beck was searching for the perfect light of Provence for artists.

His son Arnold Beck died in a traffic accident in 1981 at the age of 13. The traumatic experience plunged his father into an existential crisis. This loss tragically compounded the trauma he had already suffered from the loss of his own physical integrity and the loss of his father. In his artistic work, this resulted in a long-lasting exploration of the theme of the transition from life to death, initially in a figurative manner, then in complete abstraction. Beck can be classified as a representative of concrete art from 1960 onwards. The sculptures made of steel, Plexiglas, bronze, and stone were preceded by precise designs that stand on their own in terms of artistic merit and quality.

In 1982, Beck collaborated experimentally with conductor Hugo Käch and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra during the Stravinsky Days in an attempt to “visualize music and set sculptures to music.”

During the last two decades of his life, Beck increasingly withdrew from his surroundings in order to devote himself entirely to art in Louis Tuaillon's former studio house in Berlin-Grunewald. All of his sculptures were preceded by countless precise sketches and variations on motifs. Steel, Plexiglas, bronze, and stone became the dominant materials in his work. Early works, which had been created in plaster and wood, were translated accordingly.

Wolfram Beck died on January 10, 2004, at the age of 73 in Berlin. He was buried in the Wendt family grave in Cemetery IV of the Jerusalem and New Church on Bergmannstraße in Berlin-Kreuzberg. A metal plaque commemorates him there.

At the beginning of his career, Beck created large organic wood sculptures, portrait busts, and torsos made of concrete and bronze, followed by constructive wood and stainless steel works. Later, he worked with acrylic glass, Styrodur, and finally natural stone. His works are characterized by extremely precise forms.

His colorful, large-scale paintings also feature precise forms and are reminiscent of architecture and two-dimensional sculptural works.

Beck did not give his works titles and in later years no longer signed his drawings; he never signed his paintings. He found it irritating that a signature disturbed the precise composition, and the highly sensitive, reserved artist found it strange to sign his works with a flourish.

BETRACHTUGEN ZUM WERK, von Axel Bauer

Der Nachlass stellt uns vor ein Gesamtwerk eines enorm produktiven Künstlers. Wir sehen Skizzen von Plastiken, die Plastiken selbst – und dann wieder Variationen dieser Plastiken in anderen Materialien. Wolfram Beck hat sich buchstäblich abgearbeitet an seiner Kunst, hat Wege gesucht, Materialien in Form zu bringen und in Formen. In fast jeder Skizze, jedem Bild, jeder Plastik erkennen wir den peniblen Handwerker, den Sculpteur im besten Sinne.

It is no wonder that many of Beck's contemporaries always associated his work with architecture: correct perspective, clear forms, multi-sided views, spatiality, and effect in space.

But there is something else that can be experienced throughout his entire oeuvre: his affinity for craftsmanship, his perfectionism in execution, and his aversion to simple interpretations.

His works initially include large organic wood carvings, portrait busts, and torsos made of clay and stone. The spatial aspect is very present here, but still soft. As an organic motif, he varies bird wings or wings to an abstract, tension-filled form or as an abstract pair of wings, to which he also refers in his late work with the outstretched arms of Jesus on the cross.

In his middle creative period (around the end of the 1960s), Beck returned thematically to his artistic beginnings. (In 1951, the large health exhibition in Cologne offered him the opportunity to design several exhibits, in particular the complete representation of all human vessels). During these years, he varied his motifs at the time, drawing on zoological lithographs by Ernst Häckel, for example.

Perhaps this episode also crystallized another main theme in Beck's creative work—he wanted to understand connections—and make them understandable. Many works from this period also deal with mechanics and electronics. Components are connected in a seemingly playful manner and can be moved by the viewer using drives or by hand. The fascination of the exact sciences for the seeker and researcher, who finds himself caught between two worlds. Accuracy was at least as important to him as the effect of his works.

In addition, in this episode he creates clear and fragile-looking sculptures made of metal and acrylic, accentuated with color. He moves away from warm, earthy wood and organic materials and translates the lightness of wings into materials that appear weightless. Acrylic glass and highly polished metal surfaces create transparency. Technical components are used to enable physics to create a sense of detachment—is it a form of redemption? At the same time, the proportions always demand stability. The base is always taken into consideration.

The main feature of all his works (not only those from this creative period) is the extremely precise and careful processing and treatment of a wide variety of materials. Each motif can be found in sketches, paintings, plastic models, and also in the sculptures. One gains the impression of a seemingly endless variety of forms and motifs, which only reveal their references and contextual connections at third and fourth glance.

His paintings are becoming increasingly larger and more expansive. He creates a large number of designs in three dimensions. He pays particular attention to precise forms. His colorful, large-scale paintings in particular demonstrate this precision and are reminiscent of architecture and two-dimensional sculptural works.

Far more than the visual arts of antiquity and modernity, he finds his artistic counterpart in architecture. Looking at many of Beck's paintings, one discovers a spatial depth that makes the painting appear like a replica of a sculpture or the design for a sculpture, less as a preliminary stage and more as a two-dimensional twin. Thus, the pictorial spatiality often evokes architectural associations. It is the language of the architects of Castel del Monte and Abbaye du Thoronet, the language of Barlach and Le Corbusier, that inspires him and that he wants to speak, not knowing whether he is capable of doing so.

After the death of his son in 1981, to everyone's surprise, there was no break in the artist's productivity. But we can perceive a change in his motifs. The theme of Jesus on the cross and “wings,” which had always resonated as his echo of art history, took on a very important role in his artistic work from this time onwards. As a Bible-savvy agnostic and a skeptic trained in mythology, Beck attempted to translate the central promise of religions into images—salvation through death, the transition to a hopefully better world.

Beck varies this theme in many ways in his later work. The “gate” to the other world becomes nothing short of an obsession for him. Perhaps because he hoped that his art would enable him to see behind the scenes of death, or perhaps because he realized that worldly understanding ends at this very gate.

But through this late work, through the various perspectives on death and transition, Beck has passed on to us his view of life. That despite all obstacles, everyone must pass through this gate. And that despite his misanthropy and depression, he loved life and could not accept the death of others.

ON THE OPENING OF THE RETROSPECTIVE IN 1997, by Astrid Kuhlmey, Deutschlandradio Kultur

Der Augenblick, in dem ein Künstler seine Arbeit öffentlich macht mit der er lange, manchmal quälend, oft auch leidenschaftlich und freudvoll alleine zugebracht hat, deren Entstehen er zweifelnd oder spannungsvoll verfolgt hat, dieser Augenblick hat ein hohes Maß an Preisgabe der eigenen Biografie, so daß ich jede Beklemmung gut nachvollziehen kann. – Zumal Wolfram Beck jemand ist, dem es an quicker Leichtigkeit, belanglosem Umgang und dahergesagter Nettigkeit so ganz und gar mangelt. – Seinen Entscheidungen geht ein langes Für und Wider voraus.

That's why it's not easy for me—and I'm being honest here—to say a few words about him and his work. Wolfram is sensitive, listens very carefully, thinks about every sentence longer than I might like, hopefully doesn't misunderstand anything, and certainly goes deeper than I can here.

With this, I believe I have touched upon a significant point in his artistic biography: it is the rather melancholic landscape that shaped him as a young man, a region, at least in my opinion, that exudes a rather angular nature, whose straightforwardness does not allow for ethical maneuvering, yet always conceals a longing for carefree lightness, which Wolfram clearly feels in the southern French region.

Er sehnt sich nach den durchscheinenden Himmeln in Tourrettes und hat dort das flimmernde Grau preußischer Areale im Kopf. Kommen und Gehen, Bleiben und Verlassen – dieses ständige Koordinatensystem unseres Lebens.

When asked whether this climate zone—and by that I certainly don't mean pure meteorology—whether this atmosphere of such diverse influences affects him in his artistic work, he answered with a surprisingly spontaneous NO.

At least, I was surprised. I want to believe him, but I'm starting to have my doubts.

For can one imagine the velvety pastel chalk drawings, the elegant but brittle arabesques of some forms, without the invigorating glow of Mediterranean sunny days? I find it difficult to exclude this experience from his art.

Now, touching on the biographical, I have come to what surrounds us here in such pleasant balance.

Einige große Bilder, kaum Plastisches – obwohl es Wolfram Beck obsessiv beschäftigt – vor allem aber Zeichnungen, jenes Genre der bildenden Kunst, dem man bekanntermaßen die größte Intimität nachsagt.

Kein Druckvorgang steht zwischen Idee und Ausführung, die Unmittelbarkeit hat mitunter die Fragilität und Nähe einer Tagebuchnotiz, deren Aura man nicht ohne Strafe berührt. Man hat auch, wenn man sich eingeladen fühlt, die Vertrautheit eines Gespräches. – Also gehört Mut dazu, diese „Schriftzüge“ zu offenbaren.

What did I read?

No stories, and certainly no aphorisms.

But there is this insistent respect for form—for clean form—the pleasure derived from variation, from depth, the nobility of simplicity. No decoration, only occasional elegant arabesques—rare moments of graphic exuberance, which nevertheless remain strictly opposed to anything bizarre. At the same time, this clarity seems to me to work with a double meaning. Namely, when clear geometric forms become labyrinths, floating strangely weightless in an infinite space or forming towers whose stability is deceptive. As I said, these are not stories. This is pure form.

The art of fugue can also be explained mathematically—but who can explain its spirituality?

When I asked Wolfram when he had actually moved away from figurative, visually familiar representational art, he fell into his familiar state of contemplation.

Later, he knows for sure that he was already doing both at college:

The portrait and the nude emerged—traditional forms in the best sense of the word—and he was equally fascinated by the alphabet of geometry, the constructive, the logic of forms, and their diverse relationships.

There is the desire, but also the drama of precision, accuracy, solid craftsmanship, and depth.

He never does anything lightly; Wolfram always seeks the complicated path.

Where many of us have long since found an answer, he continues to probe, never letting anything rest. This is also how he approaches his artistic material, how he approaches his drawing paper.

It's not an easy life—no glamorous résumé as a bon vivant.

Schauen wir uns, das Konstrukt von Linien, feinsten Strichstrukturen und sich ausbalancierenden Formen an. Metallfarben, Pastellkreide, Bleistift – Blau, Schwarz, Weiß, Gold, Grau.

Slowly developing, intense ciphers.

Rising and falling are associated with the struggle between mass and lightness. The contrasts between black and white are rarely evoked with full force, but are mostly explored in a thoughtful manner.

And the drawings reveal something else: a reluctance, almost a panic, about making grand gestures. Even though today, that's usually the only thing that works...

But to whom and what?

These leaves, surrounding us, finely framed, surrounded by elegant passe-partout space, are of a truly anachronistic tranquility. They neither bluff nor rely on the slightest effect, nor do they trust the exhibitionist urge for self-expression that most artists achieve so easily.

Wolfram seems to be hiding behind his minimalist pictograms. Perhaps we shouldn't get too close to him, and perhaps we can sense more of him in his works than he thinks, than he would like?

But perhaps that is a mistake...

There is his withdrawal from what most of us believe to be the world. Wolfram sometimes reminds me a little of Diogenes in his barrel.

That was his world, his depth, his truth. And who would dispute that, for how can I justify my reality as the real one? This turning away from the external may give strength for spiritual exploration, does not need maximalist outbursts, but tests the inner essence of forms, things, signs. It seems like a concentration on the center, the essence, that which became essential to him.

That may be modesty, but not the kind whose timidity takes your breath away, which is modest without any ideas. I am thinking more of that almost old-fashioned reverence for moderation.

Und Noblesse erklärt sich – so konnte ich jedenfalls beobachten- keineswegs durch die Quantität.

Or is this almost manic focus on form a kind of escape? This withdrawal would be in keeping with Wolfram's nature.

This, too, is a test case, his variations on the theme.

One question—and many answers are possible. For him, it is a seemingly inexhaustible field in which he wanders until exhaustion. It is also a vast field, as Fontane has his Briest say melancholically. For he will never be satisfied with the final answer, the form he has found.

This drives him, makes him restless, and ultimately only finds peace in the solitude of his studio. There he circles around the form, perhaps thinking of some drawings as larger, more sculptural impressions—made of fine materials, without decorative concessions.

Most of the images, which can be understood as variations on a theme, are not based on dramatic processes; very quietly, gradually, they suggest changes one after the other—somewhat reminiscent of Wolfram's insistent questioning when he finds a situation implausible and suspects inappropriate sloppiness.

But change does not come easily—especially when it comes to one's thinking and art.

Now I have put some of my thoughts and feelings into words, but only he can judge whether they do justice to him and his work. Perhaps he will take issue with some of the sentences, disagree with them—I wouldn't be surprised. That's just like him. I expect it.